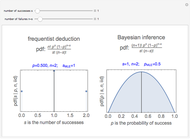

Frequentist versus Bayesian PDF for Binary Decisions Like Coin Tossing, OSHA Compliance, and Jury Trials

Requires a Wolfram Notebook System

Interact on desktop, mobile and cloud with the free Wolfram Player or other Wolfram Language products.

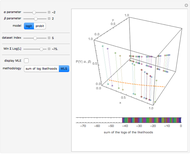

The probability of success in a single trial  , the number of trials in an experiment

, the number of trials in an experiment  , and the number of successful trials

, and the number of successful trials  are the parameters used to illustrate both frequentist deductive reasoning and Bayesian inductive reasoning. The trials are independent and identically distributed (iid).

are the parameters used to illustrate both frequentist deductive reasoning and Bayesian inductive reasoning. The trials are independent and identically distributed (iid).

Contributed by: James C. Rock (July 2012)

Open content licensed under CC BY-NC-SA

Snapshots

Details

Discussion of Snapshots

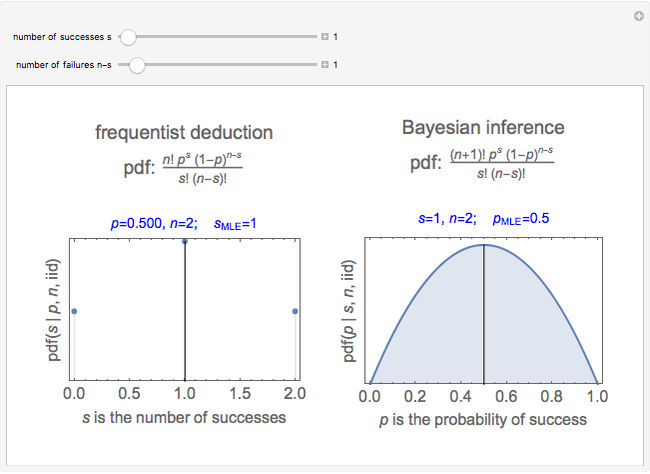

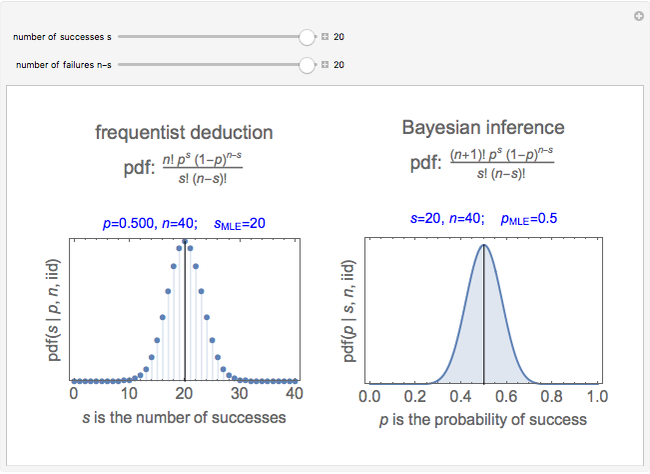

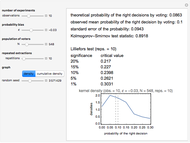

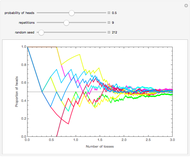

Snapshots 1 and 2 show the results from two experiments with  . The PDF is narrower for

. The PDF is narrower for  than it is for

than it is for  . Larger experiments lead to better precision.

. Larger experiments lead to better precision.

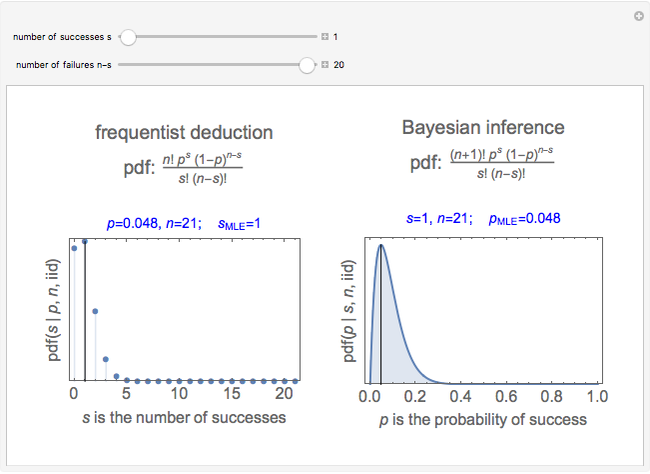

Snapshots 3 and 4 show the results from two extreme experiments, with 1 of 21 trials either failing or passing, resulting in  or

or  , respectively.

, respectively.

Snapshots 3 and 5 show results from two experiments with 1 failure in 21 or 6 trials, resulting in  or

or  , respectively.

, respectively.

Things to Try with This Demonstration

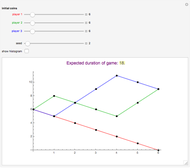

Examine the shape of  for

for  and for

and for  while

while  takes values from 1 to 20. Note that the width of the PDF narrows as

takes values from 1 to 20. Note that the width of the PDF narrows as  increases. This concept is useful for estimating the number of samples to plan for under anticipated experimental conditions.

increases. This concept is useful for estimating the number of samples to plan for under anticipated experimental conditions.

Examine the shape of  when

when  for various

for various  between 1 and 20. Note again that the width narrows as

between 1 and 20. Note again that the width narrows as  increases.

increases.

You have now observed the reality of experimental design: to improve experimental precision one must dramatically increase the number of trials in an iid experiment.

Discussion

A binary trial, sometimes called a Bernoulli trial, is one that results in one of two outcomes, variously called success and failure, pass and fail, heads and tails, comply and non-comply, guilty and not guilty, 1 and 0, true and false. The terms success and fail or comply and non-comply are used in occupational and environmental compliance decisions.

An experiment consists of  independent, identically distributed (iid) Bernoulli trials. The probability of success in each trial is

independent, identically distributed (iid) Bernoulli trials. The probability of success in each trial is  , the probability of failure in the same trial is

, the probability of failure in the same trial is  , and

, and  is a real number in the closed interval

is a real number in the closed interval  .

.

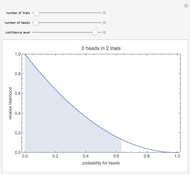

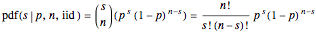

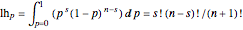

Bayes's theorem is usefully expressed with likelihoods: posterior likelihood = prior likelihood × data likelihood. In this Demonstration, the prior likelihood function is the uninformative uniform distribution, so the posterior likelihood distribution = data likelihood distribution. The data likelihood for a binary experiment with iid trials is the product of the probabilities for each trial. In this Demonstration, the data likelihood is:

.

.

This likelihood function (LHF) is the probability of any specific outcome from an experiment with  trials yielding

trials yielding  successes. It has three variables. Two of them (

successes. It has three variables. Two of them ( and

and  ) are known at the end of an experiment, while the third,

) are known at the end of an experiment, while the third,  , is not directly observed. The frequentist assumes a value for

, is not directly observed. The frequentist assumes a value for  and deduces the discrete probability distribution for the number of successes in

and deduces the discrete probability distribution for the number of successes in  trials. The Bayesian, through Bayes's theorem, uses the data to infer the probability distribution for the parameter

trials. The Bayesian, through Bayes's theorem, uses the data to infer the probability distribution for the parameter  .

.

The frequentist uses the binomial coefficient to define the number of ways  successes can be arranged among

successes can be arranged among  trials. Each of those arrangements has the same probability, which is denoted by

trials. Each of those arrangements has the same probability, which is denoted by  ,

,  ,

,  . The probability of

. The probability of  is the product of the binomial coefficient and the probability of each individual arrangement of

is the product of the binomial coefficient and the probability of each individual arrangement of  successes among

successes among  sequential trials. In conditional probability notation (deprecated by some frequentist experts, but widely used by Bayesian experts), the resulting discrete binomial PDF is written:

sequential trials. In conditional probability notation (deprecated by some frequentist experts, but widely used by Bayesian experts), the resulting discrete binomial PDF is written:

.

.

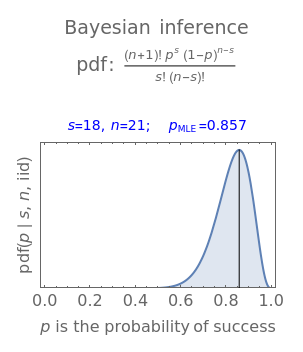

The Bayesian uses the data ( and

and  ) to infer a conditional PDF for

) to infer a conditional PDF for  and to estimate its maximum likelihood value. The area under the likelihood function, here called the likelihood (

and to estimate its maximum likelihood value. The area under the likelihood function, here called the likelihood ( ), is calculated by integrating LHF with respect to

), is calculated by integrating LHF with respect to  over the range of 0 to 1. This is the Eulerian Integral, and it has a well-known solution:

over the range of 0 to 1. This is the Eulerian Integral, and it has a well-known solution:

.

.

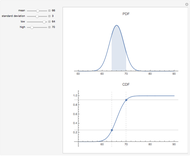

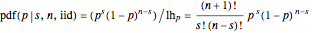

Divide the LHF by its area to find the functional form of the PDF with unit area:

.

.

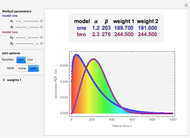

It turns out that both of these probability density functions can be expressed in terms of well-known parametric distributions. The first is the binomial distribution with independent variable  , defined by parameters

, defined by parameters  and

and  . The second is the beta distribution with independent variable

. The second is the beta distribution with independent variable  defined by shape parameters derived from

defined by shape parameters derived from  and

and  , so that

, so that  and

and . In Mathematica's notation these are expressed as:

. In Mathematica's notation these are expressed as:

=PDF[BinomialDistribution[n, p], s] and

=PDF[BinomialDistribution[n, p], s] and

=PDF[BetaDistribution[s+1, n-s+1], p]

=PDF[BetaDistribution[s+1, n-s+1], p]

To summarize, the likelihood function for a binomial experiment consisting of  Bernoulli trials is central to both frequentist deduction and Bayesian inference. To the frequentist, LHF is the probability that an experiment ends with

Bernoulli trials is central to both frequentist deduction and Bayesian inference. To the frequentist, LHF is the probability that an experiment ends with  successes arranged in one of several sequences among

successes arranged in one of several sequences among  trials. The probability of

trials. The probability of  successes in

successes in  trials, irrespective of the sequence, is expressed by counting the permutations of those trials. To the Bayesian, Bayes's theorem with the uniform distribution as the uninformative prior shows that LHF has the shape of the PDF of

trials, irrespective of the sequence, is expressed by counting the permutations of those trials. To the Bayesian, Bayes's theorem with the uniform distribution as the uninformative prior shows that LHF has the shape of the PDF of  given

given  and

and  , and normalizing it to unit area produces the desired PDF.

, and normalizing it to unit area produces the desired PDF.

This analysis produced two desired posterior distributions: the frequentist one for  given

given  and

and  and the Bayesian one for

and the Bayesian one for  given

given  and

and  . Suitable models for both of those distributions are found in the Mathematica collection of distributions. Using the binomial and beta distribution formalism opens the entire Mathematica spectrum of statistical analysis tools for further analysis of the compliance problem or any of its analogous binary decision problems.

. Suitable models for both of those distributions are found in the Mathematica collection of distributions. Using the binomial and beta distribution formalism opens the entire Mathematica spectrum of statistical analysis tools for further analysis of the compliance problem or any of its analogous binary decision problems.

References

[1] D. J. Blower, Information Processing: Boolean Algebra, Classical Logic, Cellular Automata, and Probability Manipulations, Pensacola, FL: David Blower, Third Millennium Inferencing, 2011.

[2] P. C. Gregory, Bayesian Logical Data Analysis for the Physical Sciences: A Comparative Approach with Mathematica® Support, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

[3] D. Sivia and J. Skilling, Data Analysis: A Bayesian Tutorial, 2nd ed., New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

[4] E. T. Jaynes, Probability Theory: The Logic of Science, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Permanent Citation